Measuring the health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) of a population is a concept that has been around since the late 1940s. This is when the World Health Organization proposed that health be measured, not simply by the absence of disease, but by the quality of one’s life. This is great in theory, but the reality is that quality-of-life can be a difficult thing to quantify. How do we measure gains or losses in HRQoL?

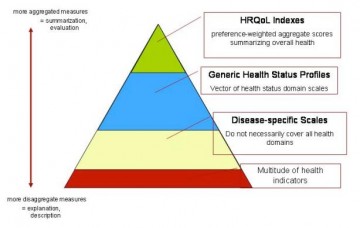

As one answer to this, Fryback (2010) presents the Data Pyramid for Population Health in a paper he authored in 2010 (see figure 1). The pyramid has four levels. On the first level of the pyramid, the base, are the crude health indicators and vital statistics, such as a population’s death, immunization, and malnutrition rates.

The three levels above this move away from indicators into more direct measures of HRQoL. The second and third levels conceptually define and operationalize measures of HRQoL, including domains of physical, psychological, and social health. The final level uses these direct measures to scale and index HRQoL.

Why measure HRQoL?

One of the main motivations for measuring HRQoL – or, more specifically, change in HRQoL – is to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention. Measuring HRQoL is important from a clinical and policy perspective. Clinicians might be interested in knowing the impact that their care is having on patients. They could use measures of HRQoL to track and monitor their patients over time, or before and after a specific intervention, like surgery.

Policymakers may be interested in learning which intervention offers the largest benefit to patients. For example, the United Kingdom’s National Health Services is using HRQoL to assess the effectiveness of hip or knee replacements, varicose vein surgery, and groin hernia surgery. They are collection HRQoL – which they term patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) – from all patients in the United Kingdom undergoing these procedures.

HRQoL: a conceptual framework

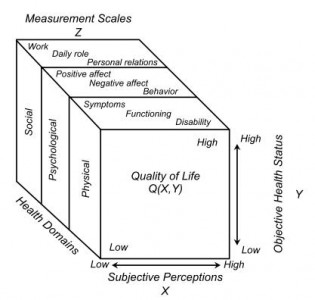

Back in the mid-1990s, Testa et al. (1996) proposed a conceptual framework for thinking about HRQoL. They define HRQoL as comprising three domains: physical, psychological, and social. Each of these domains can be measured either objectively – using clinical diagnostic data, for example – or subjectively – using patient reports and perceptions. These patient reports are usually collected on a fixed scale in order to quantify responses. This framework is reproduced in figure 2.

Objective and subjective data can be combined in order to value a given health status profile. These values can then be indexed, which in turn can be used to measure differences in health status.

Generic vs. Disease-Specific Health Status

If we go back to the data pyramid for population health in figure 1, we can see that health status can be measured on a generic basis or a disease-specific basis.

In measuring generic health status, the physical, psychological, and social domains are measured on a general basis. Such as how strong, depressed, or gregarious we feel. This general measurement is good for when we want to compare health status across different clinical conditions.

If we want to compare health status across differences diseases or conditions, then we might be interested in disease-specific health status. Many of the scales that measure this use the same three domains (but not always) but ask questions that are more specific to their symptoms, behaviour, and impairment.

These HRQoL instruments offer tremendous potential for the measurement and quantification of population health. Organizations like the National Health Services are leading the way in terms of their collection on a large scale, but other jurisdictions are watching closely and may soon be testing the waters.